|

The tears are surprisingly near the surface even now; even after 20

years.

It seems almost unbelievable that it all happened so long ago, and yet

the awfulness of that summer morning when I found my baby boy Sebastian,

dead in his cot, never wanes. The emotions can still flood back and hit

me like a hammer blow.

Over the two decades since that day, other bereaved parents and experts

have assured me that Ďthe pain fades with time, but the love never

doesí.

|

|

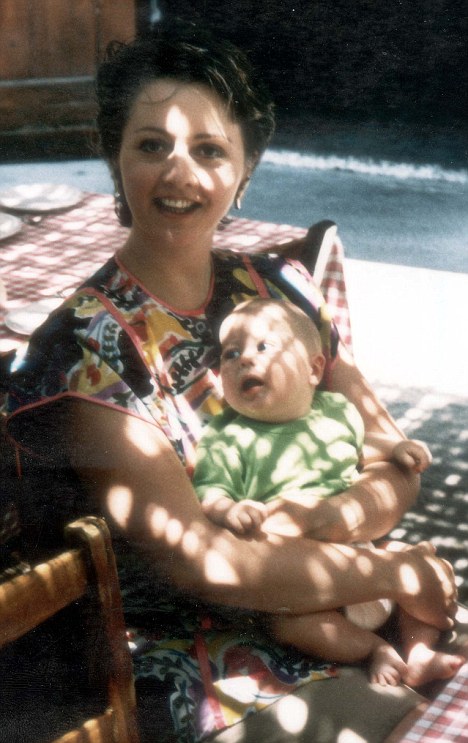

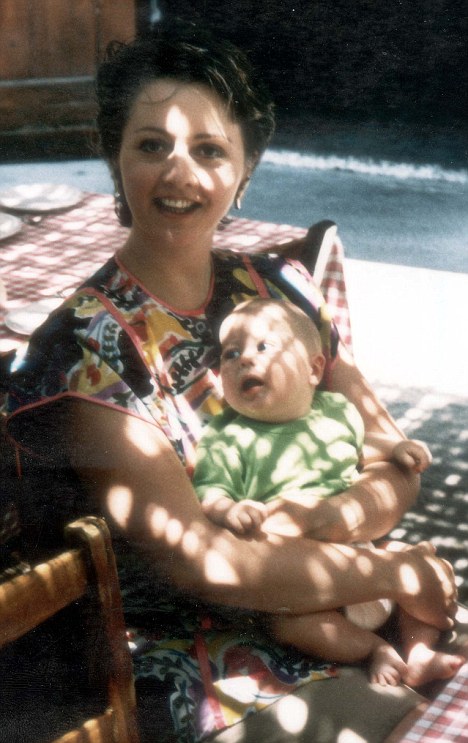

Precious

moments: Anne cuddles her healthy baby boy, Sebastian, who

died aged just four months |

I have clung to that mantra through some very dark times, and it has

helped. But as I remember the moment I helped my two older sons, Oliver

(then four) and James (just two), say their last goodbye to their little

brother, the tears still well up, my voice cracks, and the rawness of

the pain still shocks me.

Iíve constantly tried to ensure that Sebastianís life, of just

four-and-a-half months, remains larger than his death - at least to his

family. Of course, his loss in 1991, when I was a presenter on morning

television, became huge news and the focus of a national campaign to

help prevent cot deaths like his. A campaign that experts say has saved

as many as 20,000 lives.

It always makes me look back with immense pride as well as grief. My

little boyís death was not in vain.

But when the family get together, as we did just a couple of days ago,

this time to celebrate Oliverís 24th birthday in a local Chinese

restaurant around a big family table, I am always aware of Sebastianís

absence and I canít help thinking what might have been had he lived.

|

|

Grief:

Anne and Mike Hollingsworth carrying their son's tiny coffin |

I know exactly how heíd be. A tall, strapping lad with a rugby playerís

build, strawberry blond hair and a slightly freckly complexion. Thatís

the child I used to envisage when I looked into his babyís face.

Even after all this time, I know just where Iíd pick up the conversation

with him. Iíve had lots of imagined chats with him over the years. And

Iíve many times fantasised how it would be if the past 20 years were

just a horrible dream, and I woke up to find him living with us, just as

ordinarily as his brothers.

|

Please donít

think, for a minute, that I live in a constant state of

mourning, like Miss Havisham, with a cobweb-strewn nursery

upstairs and a penchant for the morbid and tragic. |

Please donít think, for a minute, that I live in a constant state

of mourning, like Miss Havisham, with a cobweb-strewn nursery upstairs

and a penchant for the morbid and tragic. Thanks to my four other sons,

I have always been determined to be a vibrant family of which Sebastian

would be proud.

But while grief - I think - never leaves you, it does mature,

like an old wine. Just very occasionally it actually tastes warm and

comforting to indulge in, but itís stronger than you think, and can

knock you back unexpectedly.

One terrible, cruel feature of Sebastianís death was that it

happened on my eldest son Oliverís fourth birthday.

One particular photo, too poignant to stick into any family

album, sums up the sorrow of that day.

I havenít seen it for years. It surfaced just a few days ago,

when I was researching for a speech I was asked to give to the

Foundation for the Study of Infant Death.

There, amid the reams of paperwork and reports, was the picture

of Oliver, taken on the day he should have celebrated being four, but

which became the day his little brother died and our world turned upside

down.

It is of him wearing an enormous policemanís helmet, looking more

perplexed than happy at the events unfolding around him.

|

|

Breakfast favourite: Anne, pictured here with co-presenter

Nick Owen, was at the height of her fame when tragedy struck |

It had

all started out so happily.

The

children had all slept well and Iíd had a lie-in until 7am. I remember

thinking how lucky that Sebastian hadnít woken early, because it gave me

time to go into the big boysí room and sing Happy Birthday to Oliver.

Then I popped into the babyís room.

I could

tell immediately something was wrong. Sebastianís arm was dangling

through the bars of his cot and he looked strangely still. The moment I

touched him, the thundering reality hit me. He was cold, and deadly

stiff.

Do you

know, you donít even scream straight away? You just try to take in a

truth thatís so terrible, your senses reel and reject, and you freeze.

Then I

snapped into real time and ran to the window to call for help.

I could

see my then husband, Mike, below, pacing out the lawn for a marquee for

Oliverís birthday party, lots of little four-year-olds coming to eat

cake.

I yelled

then - louder than Iíd ever screamed anything in all my life - and

pulled at the safety bars of the window. One bar came clean away in my

hand. I rapped furiously on the window pane and I saw Mike look up, his

face at first curious, changing within a split second to horror. I saw

him start to run. I turned back to the cot.

|

The cold of

his body was chilling - the back of his head, where I always

put a steadying hand, felt like a ball of stone. His face

seemed cruelly squashed and his flesh deadly white, except

for purple blotches where the blood had settled. |

The strange thing is, Iíd never seen a dead person before. But I

knew death - Iíd seen dead pets, long ago, in my childhood. I recognised

the hopeless, despairing numbing certainty of rigor mortis in my

darling boy. My precious, warm, milky son was now a stiff cold statue,

like a porcelain doll.

The cold of his body was chilling - the back of his head, where I

always put a steadying hand, felt like a ball of stone. His face seemed

cruelly squashed and his flesh deadly white, except for purple blotches

where the blood had settled.

I staggered back into the rocking chair, where the previous

night, just a few hours before, Iíd given him his evening feed, and I

rocked this little statue while Mike bounded up the stairs, took in the

horror, dialled 999, instructed our wonderful nanny, Alex, to look after

Oliver and James, and we waited in shocked silence for something to

happen.

It was hurting to hold him, he was so cold, but I couldnít bear

to let go.

A young policeman almost fell through the door, white with shock.

He knelt beside me and I could see his eyes were reddening. Then

a tear whitened his cheek.

ĎIím so terribly sorry,í he faltered. ĎYou see, the same thing

happened to me . . .í

|

|

'It's lovely to have a baby in the family again': After the

death of Sebastian, Anne went on to have another son |

I held out a hand to him. Mike stood back, almost unable to take

in the monstrosity of it all, and then he put an arm around the

policemanís shoulders. We all surrendered to more tears.

And so there we were, like actors in some grotesque, slow-motion

dream sequence from a morbid movie. Three grown adults weeping like

babies over a dead child, in a pastel playroom nursery on a sunny summer

morning in London.

When I look back on it now, itís almost gothic in its melodrama.

And yet there it is. It really happened. To tell its awful truth, even

after 20 years, is not to dwell on grief but to find a way to cope with

life.

|

Anyone whoís

ever been through anything this tragic knows that real life

can appear so unrealistic no film director would accept the

storyline. |

Anyone whoís ever been through anything this tragic knows that real life

can appear so unrealistic no film director would accept the storyline.

I often think of Madeleine

McCannís parents. The horror theyíve been through would have to be

watered down to become believable. It was the same with us.

My little family fled to my parentsí home in Bournemouth to get

away from the paparazzi. My dad stood watch at the garden gate with a

high-powered garden hose to fend off the long lenses. We even laughed

about it at the time. Yet it worked ó it kept the photographers away.

I asked if we could donate Sebastianís organs to children who

needed, perhaps, his corneas, his heart, his kidneys. Right away, I was

desperate that his death should mean something. We were told it wasnít

possible, since heíd been dead for hours and there would have to be a

post-mortem.

|

|

Lighting fires: After the death of Sebastian, Anne and Mike

kick-started a cot death awareness campaign |

Sky News

burbled in the corner of every room. ĎAnne Diamondís baby has died of

cot death,í the presenter said and I thought ó how come they know whatís

killed him when I donít?

So

intense was the present that the future seemed impossible to comprehend.

But life

started to go on, even though every minute felt like a betrayal. I

decided I wanted a chorister to sing at Sebastianís funeral service, and

my best friend Shirley, whoís a whizz at fixing just about anything,

managed to find a boy living nearby who was the runner-up to Chorister

Of The Year.

She got

him to turn up and sing a beautiful Nunc Dimittis, and he even brought a

fellow trumpeter with him.

Wonderful, sad, inspirational letters flooded in from the famous and

sympathetic and similarly bereaved. The former England footballer Jimmy

Greaves had been through the same tragedy himself and wrote to offer his

sympathy.

One card

was from a woman in Andover, who had lost her child to cot death, too.

She wrote: ĎThey do say time heals but believe me, Anne, you never

forget. My Robert would have been 50 now. I always have a little weep

when I go to his grave. I am nearly 77 years old.í

I

remember reading that and thinking ó will I be able to go on and one day

look back over so many, many years at Sebastianís short life and death?

Will I still feel such pain, for ever?

|

|

Sweet dreams: The number of cot deaths has reduced

dramatically in the last 20 years. Research shows that the

risk is cut if babies sleep on their backs |

And now, 20 years later, here I am. Lucky, very lucky, in some

ways because my babyís death did indeed spark a life-saving campaign. So

many others I have met lost their children when research was in its

infancy, and there were no campaigns to start, no advice to give.

But in 1991 we had indeed found a breakthrough and yet the

information had not been passed on to mums and dads in Britain.

Theyíd found in a huge national study in New Zealand, and in a

smaller study in Avon in the UK, that the babies who were dying of cot

death were those who were lying on their tummies to sleep. The truth is

that the Department of Health knew this astonishing fact and was waiting

for more data.

In fact, theyíd agreed to let British babies act as a Ďcontrol

groupí for the intervention in New Zealand, where every mum and dad was

being told to turn their baby over.

Itís a scandal thatís almost impossible to fully grasp. Our

Department of Health had actually agreed NOT to tell parents the

life-saving advice, while in New Zealand (and in Avon) there were

full-blown campaigns to save lives.

Thatís the point at which Sebastian was born, lived his short

life, and died. I still believe that if we had lived in Bristol or New

Zealand, he would be alive today.

In my anguish, I turned to everyone I could think of to get

British parents the same deal.

I even went to Jeffrey Archer, to ask how I could get to see the

then prime minister, John Major. He advised me that ministers are like

firemen. They donít have time to put out every fire, only the hottest

ones.

So I decided to make a big blaze. Thatís why I prostituted my

grief on every TV and radio programme I could, at this very time 20

years ago, to demand a life-saving campaign out of the Government. And

it worked. I got a call from Virginia Bottomley, then health minister.

Would I pop round to her offices in Whitehall?

I had trouble convincing her we needed a TV campaign. She told me

that young mothers didnít watch TV, they read baby magazines. I was

gobsmacked. Who did she think watched Richard And Judy, Neighbours, Home

And Away, and my own programme, Good Morning Britain?

I had a mailbag from young mothers who liked to breastfeed while

they watched me, and thanked me for the little clock in the corner of

the screen - it helped them time Ďten minutes each breastí!

I made my own TV ad, and with money from Mothercare we showed it

in the Coronation Street ad break. We could only afford one showing, but

it worked. The next phone call from Whitehall showed the Government had

woken up.

And that is how we eventually got the Back To Sleep campaign.

It ran on TV throughout the winter of 1991 and started saving

lives immediately.

Cot death numbers plummeted from 2,500 a year to about 300, where

they stubbornly remain even now. The Golden Rules still apply - babies

must sleep on their backs, must not be overwrapped, and smoking near

them can be deadly.

If only we could get young parents to stop smoking, the figures

could fall further. But itís hard to get that message through to a hard

core of desperately poor, often single mums who canít cope as it is.

Even more frightening is the evidence that some young mums are

beginning to talk on internet chat rooms about the fact that laying your

baby on his tummy might actually make him sleep longer, and more

soundly.

After 20 years, they seem to have forgotten the spectre of cot

death and could be putting their babies in danger, despite the warnings

theyíre given in hospital.

Perhaps it is time for another cot death campaign, to renew the

life-saving message. Donít letís wait for another high-profile death to

spur us into action.

Sebastian has no grave at which to weep. Only his father and I

know where his ashes are scattered. Thatís how we wanted it. I prefer

memories and photographs to remember him by.

One well-wisher wrote to me: ĎIf heaven is like some sort of

fantastic Disneyland, then think that Sebastian is already on the

rides!í When his death was young, that was a comfort while I needed such

emotional props.

Today, though, I think of him as the young man only his mother

still knows . . |